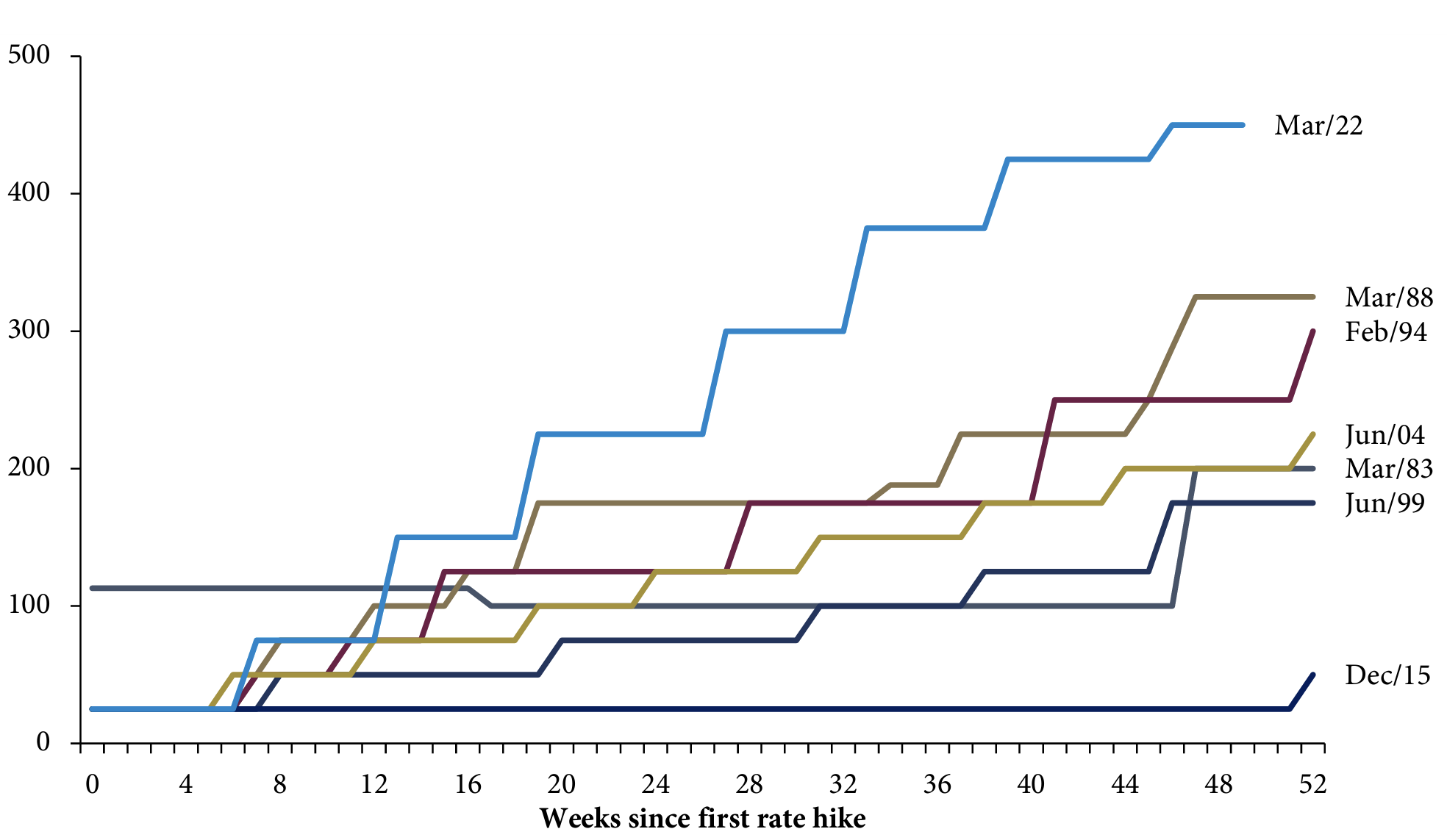

There has been a lot of attention on interest rates over the last year, and understandably so, given that 12 months ago marked the starting point for the most aggressive central bank tightening campaign in the last four decades by a wide margin.

Higher, further, faster

(change in US fed funds rate target midpoint; basis points)

Source: Guardian Capital based on data from Bloomberg to February 24, 2023

Moreover, should the increases in market interest rates seen so far this year — that have taken government bond yields to their highest levels in more than a decade — be sustained, it would mark the third consecutive year of rising rates, something that has not happened in more than 40 years.

In other words, very few current investors have experienced what is happening in bond markets in their professional lives — and there is a considerable share of the working-age population for whom it is a new experience to have borrowing costs materially different from zero.

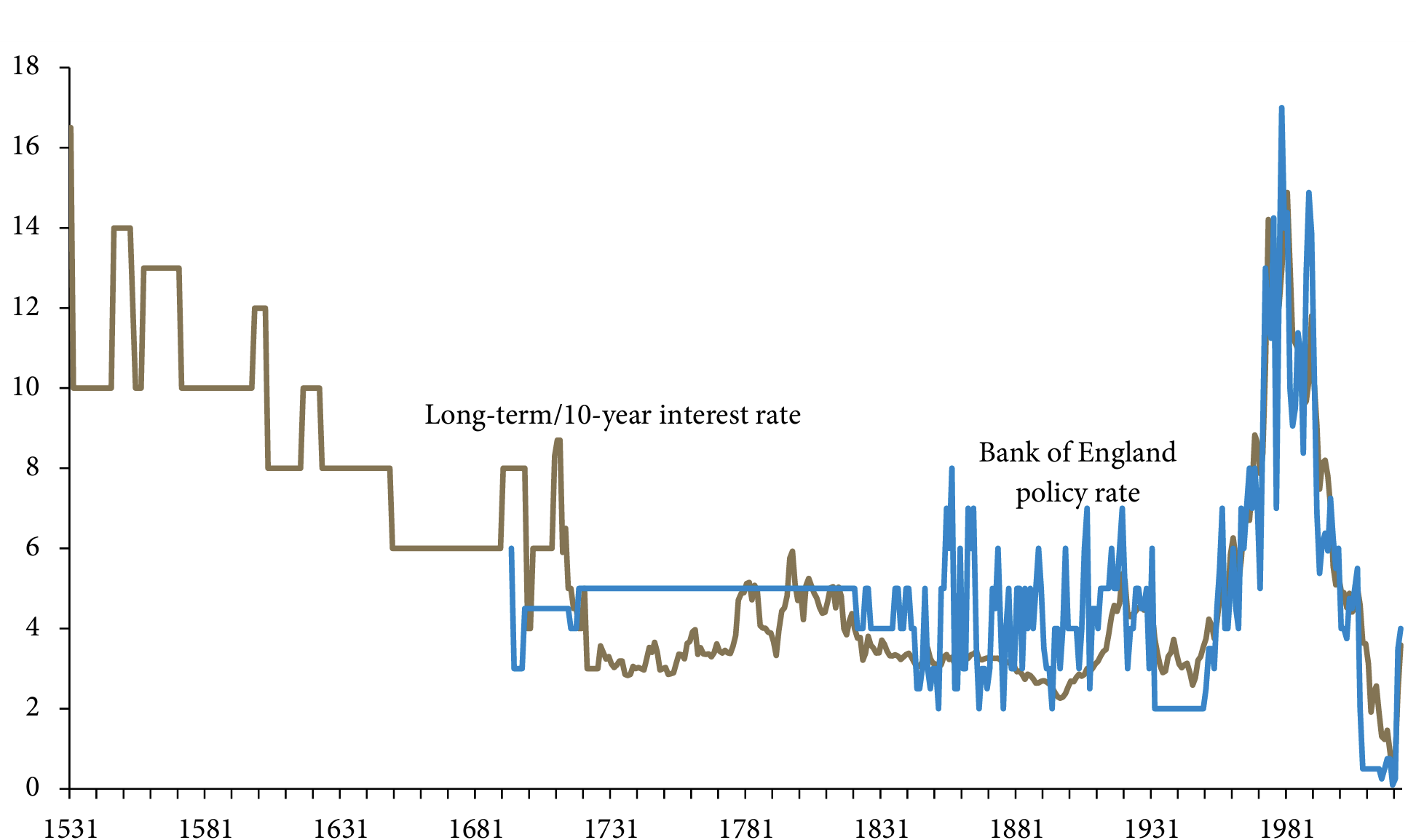

Of course, though, history shows that the last decade and a half has been the real outlier. The low level of interest rates experienced since the Global Financial Crisis — and particularly the plunge in market rates in response to the surge in monetary stimulus after the onset of the pandemic three years ago that saw a peak of 30% of bonds globally trade with negative yields — have marked an all-time low. And by all-time, that means all of human civilization effectively.

Looking at the history of “official” rates, the Bank of England was founded in 1694, and the bank rate was set at 6% upon its inception — the rate averaged about 5% over the 300 years leading up to the turn of the millennium. Before January 2009, it had never been below 2%, not during significant banking crises in the 1880s and 1890s, not during the Great Depression of the 1920s and 1930s and not during World War II. It was set at a record low of 0.1% in March 2020 and only just returned above 2% this past September.

Data and estimates for longer-term market interest rates show that costs of borrowing largely tracked those benchmark rates since their inception. Records show that bonds issued to finance integral infrastructure projects, such as American rail-roads during the boom from 1870 to 1900, had average coupons around 5%, while the US government was able to issue bonds to fund the construction of the Panama Canal at rates of 2% and 3% from 1906 to 1911 (French bonds to start the project carried coupons of 4%, initially); “Victory Loans” issued by the Canadian government to fund its participation in World War I carried interest rates between 5% and 5½%, while those to help finance World War II saw coupons from 3% for longer maturity and under 2% for those with shorter durations.

Taking a long look

(United Kingdom’s benchmark interest rates; percent)

Source: Guardian Capital based on data from the Bank of England, Measuring Worth, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and Bloomberg to February 23, 2023

Looking back before the introduction of central banks as lenders of last resort, the broad risks associated with credit translated into higher interest rates. Double-digit interest rates were common as per transaction accounts compiled by economic historians. For example, the 20,000 ducat loan to the French King Charles VIII, to fund his invasion of Italy in 1494 carried an interest rate of 14%.

Going back further still, interest rates were even higher. The first written evidence of interest rates dates back to Sumer around 2400 BC, with the going rate for loans of grain running between 20% and 50% per year — Hammurabi, a Babylonian King from 1792 to 1750 BC, established limits on interest rates of 20% on loans of silver and 33.3% on loans of grain.

This is all to highlight that the recent experience of low (and zero and negative) interest rates is historically unprecedented. To the extent that markets ultimately revert to the mean, it was only a matter of time before rates moved away from those anomalous levels — the adjustment, however, has been far less fun for investors than the reversion from the “overshoot” of the 1970s and 1980s when central bankers aggressively tightened policy to combat inflation that spurred a four-decade bond bull market.

The opinions expressed are as of the published date and are subject to change without notice. Assumptions, opinions and estimates are provided for illustrative purposes only and are subject to significant limitations. Reliance upon this information is at the sole discretion of the reader. This document includes information and commentary concerning financial markets that was developed at a particular point in time. This information and commentary are subject to change at any time, without notice, and without update. This commentary may also include forward-looking statements concerning anticipated results, circumstances, and expectations regarding future events. Forward-looking statements require assumptions to be made and are, therefore, subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. There is significant risk that predictions and other forward-looking statements will not prove to be accurate. Investing involves risk. Equity markets are volatile and will increase and decrease in response to economic, political, regulatory and other developments. Investments in foreign securities involve certain risks that differ from the risks of investing in domestic securities. Adverse political, economic, social or other conditions in a foreign country may make the stocks of that country difficult or impossible to sell. It is more difficult to obtain reliable information about some foreign securities. The costs of investing in some foreign markets may be higher than investing in domestic markets. Investments in foreign securities also are subject to currency fluctuations. The risks and potential rewards are usually greater for small companies and companies located in emerging markets. Bond markets and fixed-income securities are sensitive to interest rate movements. Inflation, credit and default risks are also associated with fixed income securities. Diversification may not protect against market risk, and loss of principal may result. This commentary is provided for educational purposes only. It is not offered as investment advice and does not account for individual investment objectives, risk tolerance, financial situation or the timing of any transaction in any specific security or asset class. Certain information contained in this document has been obtained from external parties, which we believe to be reliable, however, we cannot guarantee its accuracy. These sources include Bloomberg, Bank of Canada and National Bank Independent Network for the relevant periods cited in this commentary. Guardian Capital Advisors LP provides private client investment services and is an indirect subsidiary of Guardian Capital Group Limited, a publicly traded firm listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange. All trademarks, registered and unregistered, are owned by Guardian Capital Group Limited and are used under license.